While the 11-track album, which dropped three weeks ago, has been lauded as the sophomore follow-up to the critically and commercially successful Indigo, it is in fact Namjoon’s fourth solo excursion. Looking back to his ‘mixtapes’, RM in 2015 and Mono in 2018, it is clear to see Namjoon’s artistic journey, which starts with the youthful swagger of teenage rebellion and rap-heavy beats of his self-titled debut, before becoming more reflective and introspective in Mono and his first official solo album, Indigo. Right Place, Wrong Person sees a more confrontational Namjoon, reminiscent of his first mixtape. However, this does not mean that his latest album is a repetition of the past, but merely that an artist’s journey to self-realisation needs always to be understood in terms of the oeuvre and where the work sits within it. Of course, his solo work is always haunted by that of his other persona as the leader of the globally successful BTS, with the responsibilities that have come with it and the corresponding acclaim and continual criticism.

As Namjoon approaches 30, he is in a reflective and combative mood, commenting on his personal journey alongside the weight of the expectations placed upon him by the company, the country, and the fans. This can most clearly be seen through the multiple intertextual references to his early work on the second track on Right Place, Wrong Person, ‘Nuts’, which provides a line of continuity between the past and the present through lyrics and symbolism. When Namjoon proclaims towards the end of the track that “the monster hasn’t been me,” he is acknowledging the illusory nature of the narcissistic façade so central to his original persona – Rap Monster – as constructed on his debut mixtape. However, on ‘Nuts’, the monster is no longer the self, indeed if it ever was, and instead is the other. Further, in its direct eroticism, the track reworks the themes and motifs of ‘Expensive Girl’, a self-released track on Soundcloud in 2013, displacing youthful machismo for the adult experience. Yet this is no ode to love or desire but rather a commentary on the painful break-up of a relationship.

The mature Namjoon is no longer the inexperienced youth on the verge of possibility but rather an experienced young man whose rise to global stardom has been anything but easy. Finally, the fact that ‘Nuts’ makes reference to “stigma” in the lyric “there’s a stigma on my chest” is, therefore, no surprise, functioning both as an intertextual reference to Taehyung’s track on BTS’s breakthrough album, Wings (2016), and the weight of expectations that have comprised his artistic and personal journey from youth to adulthood. Through the constant referencing of pastness, Right Place, Wrong Person constructs identity as temporality through linguistic play as a representation of the multiplicity of the self.

On this album, Namjoon once again demonstrates that he is an extraordinary storyteller, whose aptitude in multiple languages, including English, allows him to play with words, imbuing his work with fluidity and instability, his songs an enigma that interpolates the listener to construct rather than reconstruct meaning. In these terms, Namjoon’s songs are what Barthes terms writerly rather than readerly texts, or in other words, songs that require active rather than passive reception. This is best demonstrated through the use of code-switching (language crossing) as a communicative and aesthetic device. Of the eleven tracks on the album, seven are bilingual (Korean/English) – ‘Right People, Wrong Place’, ‘Nuts’, ‘Out of Love’, ‘Groin’, ‘Lost’, ‘Come Back to Me’, ‘Around the World in a Day’one’; one is trilingual (English/Korean/Japanese), ‘Domodachi’; and the remaining three are monolingual (English): ‘Heaven’, ‘Interlude’, ‘Credit Roll.’ Further, some of the bilingual tracks use only the odd English word, phrase, or sentence (‘Come Back to Me’), while others use a much more even split between the languages (‘Nuts’), providing tonal and sonic differences in which language becomes an instrument of constant variation which is both disruptive and subversive. The use of code-switching on the album and in most of the tracks can be understood as referencing Namjoon’s multiple personae, the ‘RM’ of BTS, the ‘RM’ as a solo artist, and Namjoon, whose lived experience is constitutive of both and neither at the same time. Approaching the beginning of mandatory military service and the end of his 20s, it is no surprise that on this album, Namjoon is struggling with an existential crisis, as expressed here through linguistic and musical crossings. Or that he would collaborate with two similarly talented artists, both of whom are contemporaries of Namjoon, and are caught between cultures, struggling to find their place in society and thus share similar concerns and anxieties.

The first collaboration is with Little Simz, a multi-award-winning British Nigerian rapper of Yoruba heritage, who released her first mixtape at 14 and so far has released 4 mixtapes, 11 EPs, and five albums, on ‘Domodachi’. A song about friendship across cultures, about shared experiences and resistance to the mainstream, ‘Domodachi’ brings together UK grime, and Korean rap, infused by and through Afrobeats, while having a chorus that is sung in Japanese. The accompanying music video is directed by Pennacky (real name Kenichiro Tanaka), who at just 23 has already been named one of the most stylish video directors from Japan.

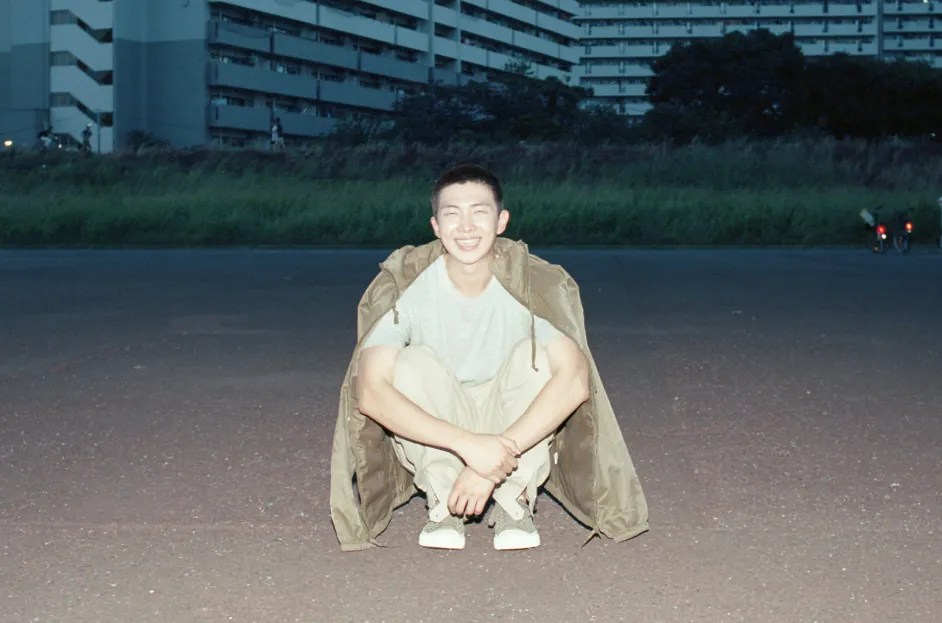

Pennacky works almost solely with artists of Asian descent, and his ambition is to see these artists globally recognized rather than confined to their locality. Shot as a condensed narrative film which metaphorically charts Namjoon’s journey from child prodigy to globally recognized artist, the film stresses the importance of friendship and authenticity in a world of inauthenticity, where money trumps artistry and self-determination comes only at a physical and psychological cost: the carefree child riding a bicycle with friends in the opening scene becomes alienated from his friends and peers and ultimately from his own self until finding a way back to the same intersection at the MV’s conclusion. As the teenager finds himself surrounded by adults, searching for a way out of the corresponding alienation and isolation, Namjoon raps: “I been slipping through all kinda bullshit; 잊었어 나의 출신/ All suckers wanna get it, take a sip 그 잔에 부어 말없이.” The chorus itself is six stanzas, and the use of Japanese here adds another texture to the track, as does the repetition of “みんな友達ここで踊りましょう(踊ります Right Now)” which translates as “Let’s Dance here, Friends (I’ll Dance Right Now),” with and without the subject in brackets. Little Simz’s verse stresses the importance of friendship and community across cultures: “Got my broski’s back til the end, you can’t put one hand on my friend / We just here for a good time everyday, 내 선은 넘지 못해.”

The second collaboration is with Moses Sumney, a Ghanaian-American artist whose interests, like that of Namjoon and Little Simz, are not confined to music, but rather are concerned with the wider aesthetic sphere in which music operates. In addition, Sumney’s work cannot be categorized to a single genre, crossing over between folk, jazz, soul, and rock, the artist seeing his name as an R&B artist as nothing more or less than racist, despite his love for the genre. While Sumney is slightly older than Namjoon and Little Simz at 32, his concerns with philosophical questions around identity, home, placement, and displacement mirror theirs. Sumney features on the 9th track of the album, ‘Around the World in A Day’ (which I would suspect will be the final music video, dropping on the 11th June). Maintaining the focus on ‘right’ and ‘wrong’, whether it is a person, a time, or a place, this track code switches between English and Korean, once again signifying Namjoon’s multiple identity positions. As we move towards the end of the album, the music becomes less angry and more contemplative as Namjoon recognizes that he can make his own path and not be constrained by the expectations of others: “내가 또 잠에 든다면 나를 좀 때려줘 / 속이 좀 안좋아 그래 그냥 좀 내려줘 / 길을 잃고 난 뒤 경치가 더 beautiful” (translation: “If I fall asleep again, please hit me / I’m not feeling well. Just let me down / The view is more beautiful after getting lost”). Getting lost here ceases to be the source of horror as articulated in the second track on the album “Lost!” and the corresponding music video by French director, Aube Perrie, which envisages Namjoon as stuck in a maze, moving from room to room, searching for the “right place”.

‘Groin’, the most confrontational track of the album, marks the transition point in Namjoon’s audio-visual search for identity and realization that in order to find himself, he must shake off the expectations of others: “내가 뭘 대표해, 나는 나만 대표해’” (What do I represent? I only represent myself). The extended chorus with its repetitions is Namjoon speaking up for himself; after all, you cannot tell others to ‘speak yourself’ if you do not follow your own advice: “Get yo ass out the trunk / You walk like a duck, bitch / Get yo ass out the trunk / Get yo ass out the trunk.” The music video which accompanies the song, directed by Pennacky, was shot on the streets of North West London using a split-screen style, with Namjoon casually dressed, spitting out bars as he navigates the dark and dismal streets of London.

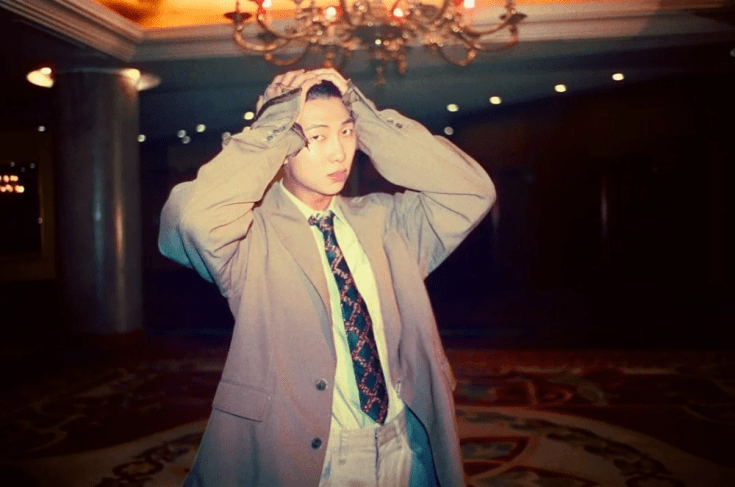

Just as the album, and the accompanying music videos, have centered on Namjoon’s search for himself, the final track ‘Come Back to Me’ ends on a hopeful note. The accompanying music video, the first to be released, is directed by Lee Sung-jin, noted for his work on the Korean drama series Beef (Netflix, 2023). The MV explores life’s connections and intersections using the multiverse as a metaphorical construct through which to visualize the possible lives of Kim Namjoon in Shakespearean style by providing a cinematic rendition of ‘All the world is a stage and all the men and women merely players. They have their exits and their entrances; And one man in his time plays many parts’ (As You Like It, 1623). In the MV, Namjoon plays different selves as he traverses a never-ending hallway, whose doors lead to different scenarios, from the past, present, and possible future. The final door, which Namjoon enters, was inaccessible at the start and can be said to signify the possibility of new beginnings. The lyrics, which end with “I see you come back to me / You are my pain, pain divine,” refer to artistic inspiration and the struggle of self-determination in a society that values spectacle over reality, an industry that treats artists as disposable, and the impossible expectations of fans.

Rating:

As an alternative rap album, Right Person, Wrong Place’s experimental beats, song composition, and overall sensibility align it with Korean indie music rather than K-pop. Further, the collaborative nature of the album and its emphasis on intercultural understanding situate it within the moniker of world music. Like his featured artists, Namjoon finds himself split between cultures, despite being Korean. The use of code-switching and genre-crossing can be said to be an artistic device through which Namjoon questions his place in the world, asking the most fundamental question of all: “Who am I?” While for Descartes, the thought itself was evidence of one’s identity, for Sartre, one’s existence was a note written on a sheet of blank paper, refreshed with every new day. Right Person, Wrong Place is Namjoon’s most intimate and accomplished album to date and a meditation on the question of identity for whom home is nowhere and everywhere. It feels the truest to the artist in its exploration of aesthetic and generic possibilities. It may well be a disappointment to some fans, who fetishize the Namjoon of the early days of BTS, but it is a musical and visionary triumph.

Rating:

Written by Dr Colette Balmain

Featured image courtesy of BIGHIT Music

View of the Arts is an online publication that chiefly deals with films, music, and art, with an emphasis on the Asian entertainment industry. We are hoping our audience will grow with us as we begin to explore new platforms such as K-pop / K-music, and Asian music in general, and continue to dive into the talented and ever-growing scene of film, music, and arts, worldwide.

Great review as always. RM is a genius – a well known fact – but never more so than in his constant translanguaging in many of the songs. The album really reflects Namjoon’s brain – a place of wonder and warmth as we all know him.

Thank you for this thought-provoking review. As a polyglot, I’ve always been fascinated by the twists in meaning moving from one language to another affords me. I never thought about the soundscape that this offers too. I think RM makes music for reflection. It’s not to everyone’s taste, but very rewarding for those who take the time to consume it.

Adding to my previous comment, this album, in the best traditions of conceptual visual art, is conceptual music. RM engages us as listeners in an intellectual endeavour making us listen and interpret his lyrics, his rapping, his melodies, his rhythms and his videos conceptually and deeply not just through sounds but through thinking and feeling.

This was such a wonderful review. I learned so much and realized things I hadn’t really noticed/thought about before. Thank you foe your incredible work. It’s so refreshing to read reviews of BTS’s work by people who genuinely get it… or at least attempt to. One thing I wish we as Army could do going ahead, is to truly set bts free. Free from our expectations and desires. Free to truly do whatever they want and we can support and back it up. We are on that path now, especially with such releases from RM and J-hope. Going forward, I really hope this is something we as a fandom can achieve. Thank you again. Looking forward to reading your other BTS reviews.